The third of four weekly excerpts from the Masterclass text, Europe and the Gospel, by Professor Evert Van de Poll. This special edition can be obtained via Schuman Resources.

EVdP: Europe is more Christian than one would have thought when looking at the visible presence of the church community. Even in the pluralist, multicultural society where secular humanism dominates the public sphere, many un-churched people maintain an indirect, often unconscious link with Christianity. Two phenomena confirm this.

The first phenomenon is called ‘vicarious religion’. The term was introduced by Grace Davie and Danièle Hervieu-Léger, a British and a French sociologist of religion. They noticed that the church embodies the collective religious memory of the whole nation, including people who do not practice the Christian religion. In this respect, the church has a function for the society at large. People appreciate that there are churches. Moreover, they see them in relation with the history of their nation. The church is part of the national cultural heritage, so the church should go on, even when they do not participate themselves.

Grace Davie has this to say: Significant numbers of Europeans are content to let both churches and churchgoers enact a memory on their behalf (the essential meaning of vicarious), more than half aware that they might need to draw on the capital at crucial times in their individual or collective lives. The almost universal take up of religious ceremonies at the time of a death is the most obvious expression of this tendency; so, too, the prominence of the historic Churches in particular at times of national crisis or, more positively, of national celebrations.

Subconscious

Related to this is a second idea in which Christianity is the ‘default religion’ of Europeans. If you are not religious yourself, but want something religious, this is the religion you turn to, as long as you do not have a particular preference for another one. Secularised people who wish a religious funeral for their deceased loved ones ask a professional undertaker to organize an eclectic mix of texts and traditions with a more or less spiritual connotation, or they request the services of a clergyman.

What is the default setting to which Europeans return when they are thinking about spiritual matters, about God, prayer, afterlife, sin, the origin of man? Two options seem to be prevalent. Either an esoteric New Age kind of spirituality and/or of elements from pre-Christian pagan religions in Europe. For this option, one needs to be a deliberate seeker of spiritual meaning.

The other option is taking up Christian traditions that linger in the collective subconscious of European people. For this option, one doesn’t have to make much effort. It is there, disseminated in our culture, to be found in any church around the corner. If you’re looking for spiritual meaning and you don’t customize, this is what you get: a Christian image of God, a Christian image of man, a Christian idea of prayer, and so on.

What about other religions? Neither Islam nor Hinduism are attractive options for Europeans in search of spirituality. ‘Old stock’ Europeans who convert to Islam almost always do this in the context of a mixed marriage. Many Europeans have a benevolent attitude towards Judaism, but in the eyes of both insiders and outsiders, this remains the religion of the Jewish people.

Heritage

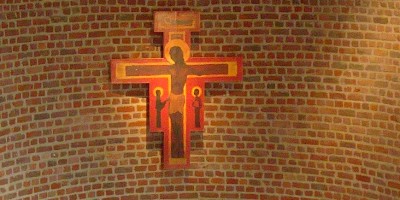

Despite massive secularisation and the development of a multi-religious society, Europe is still considered to be Christian. Christianity has left Europe with a rich cultural heritage of values, ideas and images, artistic expressions, traditions, festivals, wedding and funeral rituals, local social customs, symbols, etc. This heritage can be found everywhere. It gives a Christian ring to our national and regional cultures. And they make Europe still look Christian to outside observers.

Many non-religious people in Europe have the idea that the appropriate religion in Europe is Christianity. While they have no problem with churches continuing to function because ‘they always have,’ they are often apprehensive about the presence of ‘too many mosques.’ They tolerate them, as they think modern citizens should, but nevertheless, they feel that Islam is foreign to ‘our country,’ ‘our way of life.’

One thinks of the row over the Swiss referendum resulting in a vote against the construction of minarets; of political parties who attract voters with the message that the Muslim presence becomes a threat to our cultural heritage, saying that after all, ‘we’ are a Christian country. Public signs of Christian faith are taken for granted as part of the landscape. Secularised people actively oppose the destruction of a chapel because they consider it a beautiful element of the cultural heritage of the village.

All these examples illustrate that Christianity is seen as a normal part of the cultural landscape of Europe.

(c) Evert Van de Poll: Europe and the Gospel

Till next week,