26 july 2010

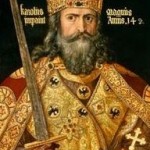

Charlemagne, Karl der Große, Karolus Magnus (literally Charles the Great) stood head and shoulders literally and figuratively above all his contemporaries. Seven times his own foot length in height (some said he was seven-feet tall), he continues to tower over the history of Europe.

His capital, the German city of Aachen, was our last stop on the Heritage Tour as we drove back to Holland from Geneva, via Basel and Strasbourg.

Today Aachen is off the beaten track, just across the Dutch border from Maastricht. It is hard to imagine that this city was once called the ‘Rome of the North’, the centre of an empire stretching from the North Sea to Central Italy, and from the Pyrenees to the River Elbe.

Thermal springs attracted the Romans to build a city on this location. Charlemagne, born in nearby Liege, adopted Aachen as his base of operations while expanding his Frankish kingdom eastwards and southwards. His military conquests included the territory of the Saxons, roughly today’s eastern Germany, and Italy from Rome northwards.

On Christmas Day, 800, Pope Leo III crowned him Imperator Augustus, emperor of a revived Roman Empire which had crumbled four centuries earlier.

The pagan Franks, who had settled in Gaul as Roman power waned, had been christianised after the conversion of their king Clovis at the end of the fifth century. Clovis’ dynasty had ruled the Franks for the next two centuries.

Charlemagne’s grandfather, Charles (the Hammer) Martel, had defended the kingdom of the Franks at the famous battle of Poitier in 732 against the invading Muslims. That Charles had begun a new dynasty called Carolingian, from Karol.

Renaissance

But it was the rule of his seven-foot grandson which became associated with the Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of education, art, architecture, politics, culture and religion in the early ninth-century, centred in Aachen.

Charlemagne’s military expansion of the Frankish empire led to what became known as the Holy Roman Empire, which continued to exist in some form until well after the Reformation.

The division of his own kingdom among his sons defined the parameters of what would become France and Germany. He was the founding father of both monarchies, listed as Charles I in the both royal lines.

Charlemagne thus helped define both Western Europe and the Middle Ages, and is often called the Father of Europe.

A visit to Aachen was therefore pivotal in our search for Europe’s soul on the Heritage Tour. Yet once more we were confronted with more of the contradictions we had often encountered on our tour, between biblical inspiration and non-biblical practice. Charlemagne’s christianisation of the Saxons at the point of the sword and his collection of concubines, for example, are hard to reconcile with his championship of God’s Kingdom.

As far south as Zurich, we had heard the story of how Charlemagne had built a church on the site of today’s Grossmunster, after his horse had stumbled on the graves of the city’s patron saints, Felix and Regula. A large statue of the emperor, sword in hand, still adorns the munster’s spire.

His stamp on the shape of the emerging Europe cannot be ignored. Under his rule, diverse peoples living in the empire were integrated; effective and efficient centralised government–civil and ecclesiastical–was developed; a common Christian faith was consolidated; and a universal currency was put into circulation.

Education

Charlemagne ordered cathedrals and monasteries to run schools for basic education. Assisted by Alcuin, the Anglo-Irish scholar-monk from York, he gathered leading scholars to develop higher education in service of a Christian society. We owe the lower case letters of our alphabet to this cultural renewal.

The glory of Charlemagne’s reign can still be seen in the breath-taking octagonal chapel, or cathedral, of the palace complex, the first and biggest Byzantine cupola north of Alps. Here the emperor still lies entombed, the epitome of the ideal ruler, the new King David. German kings were crowned there from 936 to 1531.

Today Aachen lays claim again to the imperial heritage as the bestower of the Charlemagne Prize to outstanding contributors to Europe; including Queen Beatrix, Vaclav Havel and Andrea Riccardi of St Egidio.

Till next week,

Jeff Fountain

Till next week,