Salons in Paris and coffeehouses in London, Vienna and other cities were the most important places for developing ideas that shaped public life in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

They offered informal space for interaction for people from different backgrounds without regard to rank. Women were usually the leading figures of the Parisian salons. The establishment in 1618 of Madame Rambouillet’s salon, known as le Chambre Bleue (the Blue Room), became a model for many other hostesses to hold serious and intellectual salons for invited guests.

Here Enlightenment ideas were exchanged and refined that found their way into other spheres of public life–politics, law, education, religion, arts and literature– greatly shaping our modern age.

Jerome, the early church father of the 4th and 5th centuries, wrote of a much earlier Christian model of salon in Rome in the households of influential women such as Marcella and Paula–informal centres of biblical learning, discussion and devotion.

Ideas continue to shape Europe’s present and will continue to shape the future. Today social media and television talk programmes provide the major forums for the exchange of ideas. Yet often they remain impersonal, distant or faceless.

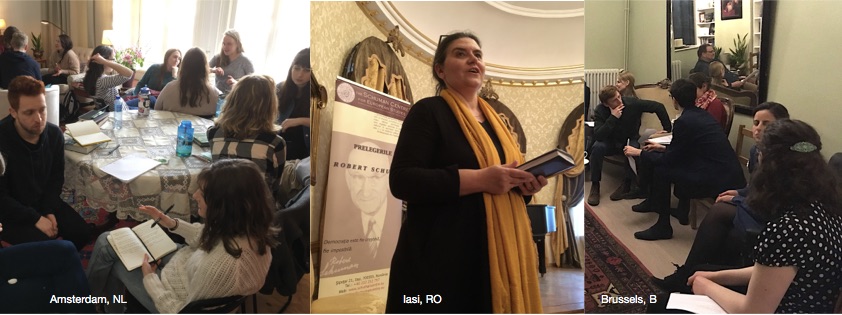

Schuman Centre activities include salon-type gatherings and settings to explore face to face the ideas that shaped our society in the past, and to seek ways biblical truths can reshape our future.

Lead roles

As in the Parisian salons, women are taking lead roles in these events. In Iasi, Romania, this past weekend, Mari Blaj and Lavinia Besliu, two Schuman associates, introduced salon-type gatherings in stately environs examining the roots of today’s crises in democracy and society. Dr John Hess addressed the Robert Schuman Lecture on the Polish philosopher Michael Polanyi, whom Francis Schaeffer described as a man ahead of his times. Polanyi, the subject of John’s doctoral dissertation, saw the internal contradictions of modern secular liberalism and pleaded for an understanding of truth beyond mere senses. We believe more than we can prove, he argued, and know more than we can say.

In Brussels, our Schuman colleague Kathia Reynders has repioneered the concept in the Schuman Salon neighbouring the European Commission buildings. This will be the venue for a series of three monthly Saturday seminars (Mar 17, April 21, May 26). In this European Studies Course, we will explore the ideas that shaped Europe’s past, tracing through the centuries to the present challenges, and finally considering possible future scenarios.

In Amsterdam, my wife Romkje has been putting the finishing touches to the salon opposite the Central Station above the Dwaze Zaken cafe at Prins Hendrikkade 50, called the Upper Room. The salon was buzzing a few days ago with a YWAM school from Norway with whom I shared sessions on understanding Europe today. Romkje and I will also host in The Upper Room a repeat of the European Studies Course from Brussels (Mar 24, April 14, May 12).

Jogging memories

Unlike the salons of Paris, no one needs an invitation and all are welcome to join these courses in Brussels and Amsterdam. Like the salons, we plan a variety of activities in coming months – including chamber music, book discussions, film evenings, bible courses and Schuman lectures.

As I shared on Saturday in Iasi, Robert Schuman’s ideas have been hugely influential on the course of Europe’s development since World War Two. Yet they remain largely forgotten or misinterpreted. We need our memories jogged on what he understood to be essential for the rebuilding of post-war Europe.

Schuman, acknowledged ‘father of Europe’ by the European Assembly for his role in launching the European project, believed it was essential that this project not remain an economic and technical enterprise. It needed a soul, which he understood to be rooted in the Christian values on which Europe had developed. Europe needed to become a community of peoples deeply rooted in these values of freedom, equality, solidarity and peace.

Democracy, he wrote in what sounds like overstatement to modern ears, owed its existence to Christianity (‘For Europe’, p43). ‘Loving your neighbour as yourself’ was a democratic principle which, applied to nations, meant being prepared to serve and love neighbouring peoples.

In Schuman’s understanding, the roots of true democracy–the principle of equality, the practice of brotherly love, individual freedom, respect for the rights of the individual–all came from Christ’s teachings.

‘Democracy will either be Christian or it will not be. An anti-Christian democracy will be a parody which will sink into tyranny or into anarchy.’

‘The European movement will only be successful if future generations manage to tear themselves away from the temptation of materialism which corrupts society by cutting it off from its spiritual roots,’ he wrote.

Democracy in parts of Europe today is edging towards tyranny or anarchy. Polanyi foresaw our predicament. These are truths that matter and conversations we need to have.

Come join us.

Till next week,