In 600 years, no pope had ever done what Benedict XVI did almost ten years ago. He resigned.

The day after his abdication, I happened to be passing through Cologne among the crowds of visitors to the cathedral, once the world’s tallest structure. The retired pope was waving from a huge photo hanging on a building opposite. One word underneath expressed appreciation on behalf of millions around the world : ‘Danke’.

To which I then added a hearty ‘amen’. And again a decade later, I join the millions around the world to say ‘danke’ to the 95-year old pope emeritus who died on New Years Eve.

I am not a Catholic, and don’t see eye to eye with all the controversial pontiff stood for. While he was a brilliant theologian, the role of pope did not always rest easily on his shoulders. Yet I am deeply grateful for all that Joseph Ratzinger did for the Christian faith over his nearly eight years as pope, and prior to that as perhaps the world’s most influential, if often misunderstood, living Christian thinker.

Protestants and Evangelicals can be thankful for his legacy for at least four reasons.

- His emphasis on the Word of God:

In December 2008 I wrote about the three-week synod for which Benedict had summoned bishops from around the world to Rome to discuss how to promote prayerful reading, understanding and proclamation of God’s Word. ‘Luther would have been amazed at the efforts of the Vatican today to put the Bible back into the heart of the Roman Catholic Church,’ I suggested then. The pope himself kicked off the synod with a round-the-clock Bible-reading marathon lasting a whole week, by reading the opening verses of Genesis. Twelve hundred readers took part, including actor Roberto Bellini (La Vita e Bella) and tenor Andrea Bocelli, as well as Orthodox and Evangelical leaders.

Benedict personally led the way to encourage Catholics to engage with Scripture. The theme of the synod was The Word of God in the Life and Mission of the Church. The pope told the gathered bishops that true reality was to be found in the Word of God. Many had put their trust in money as the true reality, observed the pope, but this was evaporating in the current global financial crisis. The Bible Society of the UK helped the Vatican promote the reading of Scripture through their Lectio Divina Project.

- His acknowledgement that, after all, ‘Luther was right’:

My wife and I happened to be in St Peters Square, Rome, a few weeks after the synod, where the 20,000 chairs for the public audience the pope had held that Wednesday were still laid out. On our return to Holland the newspaper headlines told us what the pope had told the gathered faithful that November 19, 2008: ‘Pope quotes Luther: Sola Fide‘.

The papers may have been less nuanced than how the pope might actually have expressed it. Luther’s phrase, ‘Sola Fide – faith alone‘ was true, he told his audience, if it was not opposed to faith in charity, in love. Faith was looking at Christ, entrusting oneself to Christ, being united to Christ, conformed to Christ, to his life. Yet, the pope had said, it was indeed biblical to say, as did Luther, that it was the faith of a Christian, not his works, that saved him. Such faith however could not be separated from love for God and for neighbour, he qualified. True faith, in other words, implied becoming more Christlike.

Disagreement over the doctrine of justification had been at the heart of the Reformation in the 16th century, splitting Christianity in western Europe. Benedict’s greatest legacy may be his role in bridging this great rupture in Western Christendom known as the Reformation. For, more than anyone else, the then-Cardinal Ratzinger was responsible for the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (JDDJ) of 1999, when the Catholic and Lutheran churches were reconciled over the doctrinal dispute triggered by the Wittenberg monk. As the prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Ratzinger was Rome’s chief negotiator with representatives of the Lutheran World Federation. When at one stage talks in Augsburg reached a stalemate, Ratzinger invited his Lutheran counterpart to spend the weekend with him at his brother’s house in Regensburg, less than two hours’ drive away. On their return they were able to table the proposal on which the final declaration of 31 October, 1999, was based. The World Methodist Council, the World Communion of Reformed Churches and the Anglican Consultative Council have also since adopted or ‘affirmed’ the JDDJ.

- His engagement with ‘rootless’ Europe:

While his predecessor John Paul II had contended with communism, Benedict engaged the church with secularism, relativism and Islam in 21st century Europe on a level unmatched by any Protestant or Evangelical church leader. The root-cause of the intellectual, spiritual and social crises in Western culture as he saw it was rootlessness. In ‘Without Roots’, one of his first books published during his papacy, he and his co-author Joseph Pera, the then-president of the Italian Senate, portrayed the future of a civilisation which had exchanged its own heritage and inheritance for a pot of secularist broth. In his quiet professorial manner, he warned about the consequences of embracing a culture of death: e.g. abortion, euthanasia, suicide, drastically falling birthrates and non-reproductive re-definitions of ‘marriage’.

In several key addresses, he countered the popular idea that faith and reason were incompatible and antithetical. To those who accused religion of being the source of all violence, he acknowledged that phases of history indeed showed ‘pathologies of faith’, when religion was misused to justify brutality and inhumanity. But the twentieth century alone, he argued, furnished overwhelming evidence of ‘pathologies of reason’ when so-called ‘scientific’ theories had resulted in suffering for many millions.

Again and again he returned to the problem of reason estranged from faith, a reason which deconstructed reality to that which was scientifically measurable. In his controversial 2006 Regensburg lecture, the point of which was largely lost in the global uproar by offended Muslims who did their best to prove his very point, he was actually addressing former colleagues of the science faculty at his former university on the relationship between faith and reason. John’s gospel, he said, opened with: In the beginning was the ‘logos’… and the ‘logos’ was God. ‘Logos‘ meant both reason and word, a reason which was creative and capable of self-communication, he explained. Acting unreasonably therefore contradicted God’s nature.

In ‘Europe, today and tomorrow (2004), explored the interaction between the ‘three legs’ of the cultural stool on which the ‘West’ rests: Athens, Rome and Jerusalem. When the Jerusalem leg is kicked out, the Athenian leg of reason gets wobbly.

The dialectics of secularisation, published the year before becoming pope, records Ratzinger’s dialogue with secular philosopher Jürgen Habermas, and surprised many by the degree of common ground found. It prompted Habermas’ statement that secularised citizens must not ‘refuse their believing fellow citizens the right to make contributions in a religious language to public debates’.

4. His focus on ‘hope’:

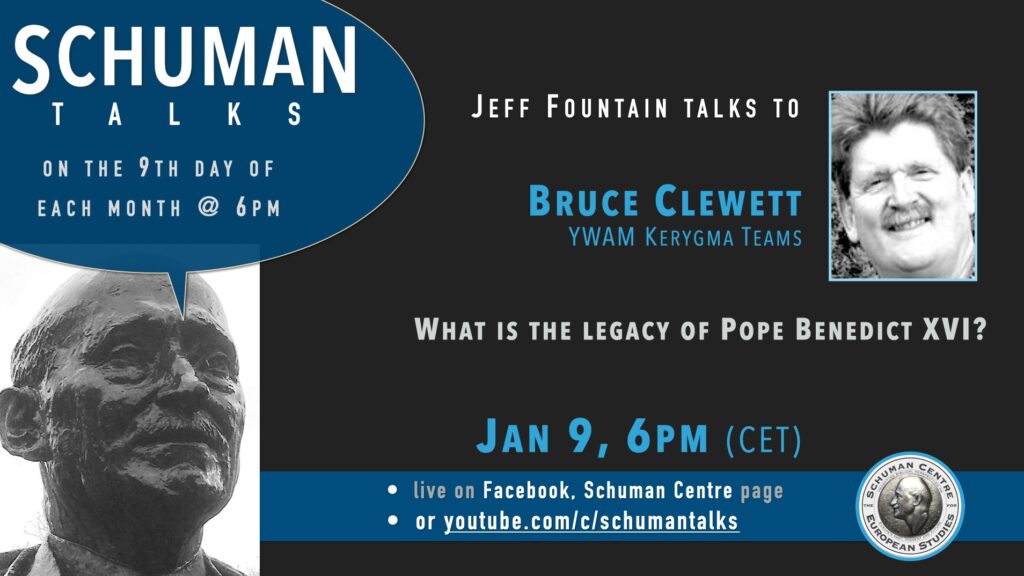

In 2006 I unexpectedly was introduced to the pope after his public audience in St Peter’s Square. My Catholic companion had urged me to dig out of my bag a copy of my book, Living as People of Hope, to present to the pontiff passing our way (see photo above). A Norwegian journalist had already drawn my attention to overlapping themes of hope and restoration in both my book and in ‘Without roots‘, which I had not yet then read. ‘Hope! That’s what we need!’ said Benedict emphatically as his eye fell on the book’s title while he shook my hand.

Benedict’s second encyclical, ‘Spe Salvi‘ (2007), begins with Paul’s reminder to the Ephesians that they previously had been ‘without hope and without God in the world’ (2:12). Now they had become people with a future. Life would not end in emptiness. ‘The dark door of time, of the future, has been thrown open. The one who has hope lives differently; the one who hopes has been granted the gift of a new life,‘ wrote the pope. ‘Only when the future is certain as a positive reality does it become possible to live the present as well... Man needs God, otherwise he remains without hope.’

Creative minorities

Benedict should be remembered for what he was for, not for what he was against. He strove to prepare his people to become a ‘creative minority’ acting as memory, conscience and imagination in a post-Christian world. In ‘Without roots‘, Benedict wrote: ‘We do not know what the future of Europe will be… The fate of a society always depends on its creative minorities. Christian believers should look upon themselves as just such a creative minority, helping Europe to reclaim what is best in its heritage and thereby to place itself at the service of all humankind.’

Amen!

And again, danke Benedict!

Till next week,