Liberation Day was celebrated on various days across Europe this past week to commemorate the end of the last World War. The official slogan here in the Netherlands was: ‘Pass freedom on!’ The irony seemed to go unnoticed that this celebration came just four weeks after the Dutch voted (well, most of those who bothered to vote) not to pass freedom on to the Ukrainians.

Jonathan Sacks too has warned about the paradox of freedom, and how that those who have never lost it tend to take it for granted. Historically, he points out, freedom has led to licentiousness, which in turn led to chaos, which further led to tyranny. ‘The paradox of freedom’ is the theme of this year’s State of Europe Forum happening yesterday and today with over 100 European participants in the Zuiderkerk in Amsterdam.

Yesterday at a Celebration of Freedom, the public opening session of the Forum, we explored the spiritual roots of freedom, and what happens when we cut ourselves off from those roots. Amsterdam, as everybody knows, is a city with a reputation for freedom. New York Times writer Russell Shorto calls it the most liberal city in the world. Where did that freedom come from?

Through a varied programme with a jazz combo, an African choir, visual screenshows and short TED-type talks from Mink de Vries and Vishal Mangalwadi, we traced Amsterdam’s DNA of freedom back to William of Orange and further, through Erasmus and the Modern Devotion movement, to the Bible.

For two hundred years before the French Enlightenment, the father of the Dutch fatherland made what was considered a shocking statement for a member of the aristocracy: ‘I cannot condone that rulers desire to rule the conscience of their subjects, removing their freedom of faith…’

William’s stand led to the Dutch Revolt and the Union of Utrecht, the covenant between the seven rebelling provinces signed in 1579, which enshrined the following: ‘Each person shall remain free, especially in his religion, and that no one shall be persecuted or investigated because of their religion.’

Unique

The resulting religious freedom of the Dutch Republic was unique in the world. It promoted stability, harmony and innovation and made Dutch culture the most progressive and diverse of its time. This freedom attracted many refugees and migrants, exploding Amsterdam’s population, wealth and influence in the Golden Century.

Jews and other refugees from Antwerp and France, including some 100,000 Hugenots fled to Amsterdam and the Dutch Republic. As did English dissenters, including the first Baptists and the Pilgrim Fathers.

Traders came from Armenia, Turkey, Iran, Syria, Russia and the Baltics, bringing their flamboyant dress, foreign languages and different religions. René Descartes, the French philosopher who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic asked: ‘In what other country could find you such complete freedom?’

But who shaped William of Orange’s thinking? Very clearly–Erasmus. He quoted him at times verbatim: ‘In a free state, tongues too should be free’.

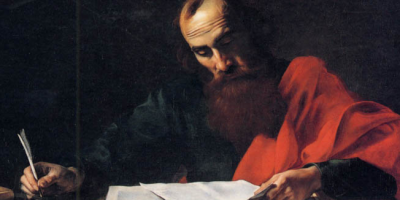

Erasmus! On this 500th anniversary of this scholar’s production of a Greek-Latin New Testament, we are learning how profound his influence was in shaping our modern world. Not only did this Bible translation lead directly to Luther’s German Bible, Tyndale’s English Bible and the first printed versions of the French, Spanish and Dutch Bibles, now we see he stood at the cradle of the free society.

Source

Erasmus was educated by the Modern Devotion movement. He attended school in Deventer where Geert Groote founded the movement. From there it spread to some 400 locations in North West Europe, bringing major changes in education, church and society. Amsterdam was a major centre of the movement. Almost all of the 22 monasteries adhering to its emphasis personal and simple devotion, prayer and bible reading. Values including equality, solidarity, cooperation, compassion, free choice, tolerance and responsibility shaped their spirituality.

Which source did Erasmus draw his seemingly radical ideas from? He was very outspoken about this. He urged princes and popes, kings and kaisers to go back to the same source: AD FONTES! Back to the Gospels, the letters of the Apostles, and the teachings of the early church fathers.

As Vishal Mangawadi, speaker at yesterday’s celebration, wrote in his book, ‘The Book that Made your World’: ‘Although Renaissance Humanists (like Erasmus) read, enjoyed, quoted and promoted Greek and Roman classics and Islamic scholarship, their peculiar view of humanity came out of the Bible in deliberate opposition to the Greek, Roman and Islamic thought. The Renaissance’s new vision of man was inspired by the ancient church fathers. Their view of man, in turn, was derived from the first chapter of the Bible: “Then God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.’”

When we cut ourselves off from this understanding, we undermine the basis for human rights, laws of justice and the truly free society.

Till next week,