Three politicians, a Frenchman, a German and an Italian, walked into a monastery chapel, knelt at the altar and began to pray fervently for the future of Europe.

This may sound like the beginning of a joke, but the three men had never been so earnest in all their lives. Exactly seventy years ago today, the politicians’ prayer retreat marked the beginning of seven decades of unprecedented peace in Europe.

For Robert Schuman, Kondrad Adenauer and Alcide de Gasperi were on their way to Paris to sign the treaty which birthed the European Coal and Steel Community, which eventually has led to the European Union. Each was a devout believer and believed God’s will was for post-war Europe to be rebuilt on ancient gospel truths and foundations; as Schuman expressed it, to become a ‘community of peoples deeply rooted in basic Christian values’.

The monastery was the famous Maria Laach Abbey, west of the Rhine as it flows past Koblenz, Neuwied and Andernach in the Eifel region. From there, Schuman, the French foreign minister, Adenauer, the first chancellor of Western Germany, and De Gasperi, the Italian prime minister, travelled to Paris some 500 kilometres to the southwest for the signing ceremony with their Benelux counterparts on April 18th, 1951.

Death threats

Maria Laach remains a most imposing example of eleventh-century Romanesque architecture with multiple towers and cone-roofed cupola. Konrad Adenauer had found sanctuary there in 1934 after the Nazis sacked him as mayor of Cologne for refusing to fly the swastika flag from the bridges across the Rhine. Facing death threats, he fled to Maria Laach, despite Nazi sympathies shared by some of the monks of the abbey including the abbot himself.

One of the role models for Schuman in his youth had been the Benedictine Abbot Bentzler of the Maria Laach. When Schuman’s mother was killed by bolting horses at a wedding in 1911, young Schuman contemplated ‘leaving the world’ to enter the priesthood. The quiet lifestyle of devotion, contemplation and study was to appeal to him all his life long. A friend’s advice that ‘les saints de l’avenir seront des saints en veston’– the saints in the coming age will be saints in suits – was for Schuman divine encouragement to ‘aid atheists to live rather than Christians to die’. He studied law and then went into politics.

Modern European history could have been very different had Schuman then decided to join the monks of Maria Laach, for example. Instead, he and his two fellow politicians had been inspired by the Church’s social teaching to search for a path of peace for a Europe suffering severe post-trauma stress disorder, a Europe torn apart by hatred, violence, deceit and bitterness. They had come to understand that the only way forward was forgiveness and reconciliation, mutual trust, accountability and cooperation, and a choice for the common good of all based on a recognition that all humans reflected God’s image and stood equal before their Maker.

This understanding gave them the courage to begin the long path towards European integration. Fellow Christian Democrats were to provide most of the support base for this developing integration process, with strong encouragement from the Vatican and Catholic laity.

Common ground

Although religion is often ignored as a significant factor in the integration process, research indicates that elites in Catholic countries (regardless of their own affiliation) show the strongest support for integration, with those in Orthodox countries next, followed by those in ‘mixed’ nations, with elites in Protestant nations being the most sceptical.

Protestants and states with Protestant backgrounds, on the other hand, have consistently resisted sharing sovereignty with federal institutions. Britain, Denmark, Sweden and Finland were all late-comers to the EU, while Norway, Switzerland and Iceland have never joined. Mainstream Protestant churches also showed little enthusiasm for what was perceived as a ‘Catholic project’, until after Vatican II. Protestants often felt that integration meant undoing the freedom of worship that their forefathers had fought for against Catholic forces. Others equated Rome with Babylon, the pope with the anti-Christ and Brussels with the Beast of Revelation.

With the secularisation of Europe, Catholics and Protestants have rediscovered much common ground, even agreeing that Luther was right about the doctrine of justification. Today Catholic and Protestant church representatives meet together regularly for official dialogue with European Commission officials. Evangelical representatives have also been lobbying in Brussels for religious freedom and other issues for nearly three decades now.

The realisation that ‘loving your neighbour’ is an imperative to choose for the common good of all across national boundaries has also been growing in evangelical circles. Secularists may find it hard to recognise, but the religious backgrounds of European nations remain a strong factor in the integration process which started with three men in a prayer retreat seventy years ago.

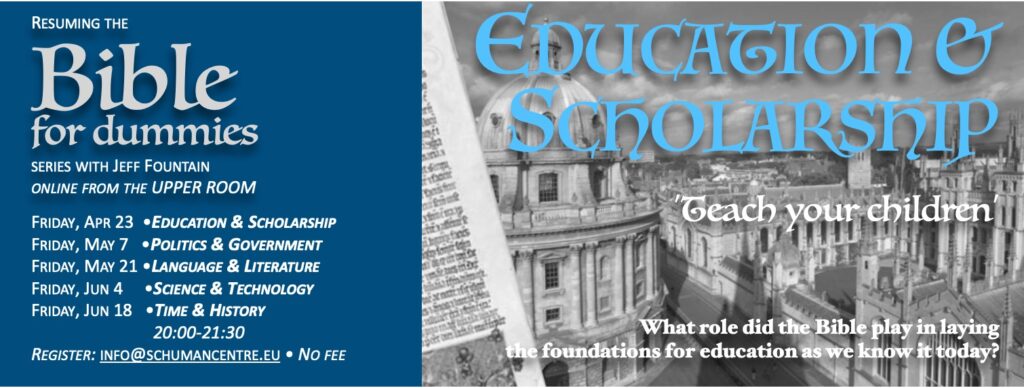

P.S. Join us on Friday @ Bible for Dummies

Till next week,